The Spanish-American War of 1898 was a turning point that dramatically changed America. The United States once had been the avowed enemy of empire. Prior to the war, president Grover Cleveland rejected war with Spain over the last pieces of her crumbling empire. William McKinley, his successor, said he would follow the same policy. In his inaugural address, McKinley, a civil war veteran, said, “We want no wars of conquest. We must avoid the temptation of territorial aggression. Arbitration is the true method of settlement of international as well as local differences.” (i)

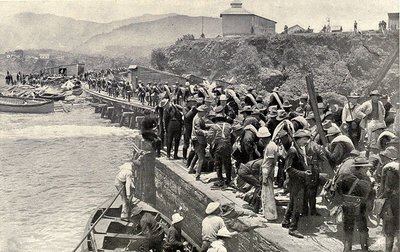

But McKinley, over the next few years, reversed himself. This is a pattern of about faces that we will often see in this series. America, in the Spanish-American War, embraced empire and celebrated the war. The war’s justification was ostensibly to liberate Cuba from Spain, although the U.S. also took the Philippines. That led to a succeeding war that lasted over a decade as Filipino rebels, who had helped the Americans against the Spanish, soon turned against their new American imperial masters. (ii) They believed that America broke its promise of freedom. That led to a horrible guerrilla war that lasted more than a decade. It was a war in which tens of thousands of Americans, rebels and civilians died.

The U.S. Army sometimes resorted to torture. “I want no prisoners,” General J. Franklin Bell told his troops. (iii) “The more you kill and burn, the better it will please me.” (iv) This horrified some Americans who organized the anti-Imperialist League. Its members included writer Mark Twain and philosopher William Graham Sumner. The United States, Sumner noted, had actually lost the war with Spain.

“We have beaten Spain in a military conflict, but we are submitting to be conquered by her on the field of ideas and policies,” Sumner wrote. (v)

The war was avoidable.

How did America go to war?

Spain, with myriad internal and foreign problems, the last remnants of her ramshackle empire falling apart, in 1895 faced still another revolt in Cuba, one of her few remaining colonies. Spain employed inhuman measures to beat the rebels. The rebels, who have been fighting without success off and on for decades, also used gruesome tactics. However, the rebels won the war outside the battlefield in the United States. They lobbied Congress. They placed reporters on some American newspapers. Tabloids made a bad situation worse.

Indeed, a Pulitzer publication, “the World,” which also had been pushing for war, accused a William Randolph Hearst’s paper, “the Journal,” of distorting the news. “The Spanish in Cuba have a lot to answer for, as the World was first to show, but nothing is gained for the Cuban cause by inventions and exaggerations that are past belief,” the World wrote of the Journal as the war fever was stoked by Hearst and others. (vi)

Truth became a casualty of war.

“You furnish the pictures. I will furnish the war,” wrote Hearst when his illustrator told him that Cuba was peaceful. (vii) Hearst accused those who wanted to negotiate a settlement as being more interested in making a buck than in patriotism. There was some logic in this critique. Many of the members of the Anti-Imperialist League were merchants. They believed trade, not war, was the great civilizer. (viii) Economist Joseph Schumpeter shared that feeling. “Wherever capitalism has penetrated,” he later wrote, “peace parties of such strength arose that virtually every war meant a political struggle on the domestic scene.” (ix)

Despite media pressures, Spain, facing a stalemate in Cuba as well as problems in the Philippines, eventually offered to negotiate just before the war with America. Indeed, at the outbreak of the war, a new liberal ministry headed by Antonio del Canovas, had virtually granted autonomy to Cuba. It wanted Cuba to have the same rights as Canada, which had dominion status within the British Empire and was working its way to virtual independence. (x)

So, just as a peaceful solution was achievable, the United States declared war. (Here was a repeat of the useless War of 1812. Congress, in a narrow vote, declared war just as the main cause of war, the British government’s hated Orders in Council, restricting trade, requiring a licensing system and allowing the British to stop American merchant ships, were revoked. They were removed at the insistence of British merchants. One crazed British merchant shot the prime minister, Spencer Perceival. Their counterparts in New England also wanted peace. They were reluctant to answer President Madison’s call for troops. (xi) The slaughter of the Battle of New Orleans happened after a peace treaty had been signed. Many people were shot, scalped and died without cause).

With the United States in the midst of a depression in the early 1890s, with congressional elections and the election of a new president coming up in 1896, some republicans, looking for an issue, embraced jingoism. (xii) But so did several major democrats. Distracting voters from domestic problems through the creation of fake foreign crises is an old trick, one that had repeatedly been played by Bismarck. Still, members of Congress and elements of the press argued for a more aggressive foreign policy through freeing Cuba. An assistant secretary of the navy, Theodore Roosevelt, not only looked to Cuba, he also pushed for the United States to take the Philippines.

Theodore Roosevelt was a man who gloried in war, which put him in the traditions of many Prussian leaders. (xiii) Roosevelt thought the country needed a war. Indeed, Roosevelt, along with Hearst, was called a “war lover” in a recent book. (xiv) One of his colleagues said he was “obsessed with his love of war and glory of it.” (xv) Roosevelt, in his own words, thought war would benefit the American people. It would give them “something to think of which isn’t material gain.” Here was a sentiment later confirmed by Joseph Schumpeter and others who see material gain and trade as the opposite of war. Roosevelt later argued that it would have been a disgrace if the United States hadn’t declared war on Spain. (xvi)

But, as we have already seen, Spain in 1898 was ready to resolve the Cuban crisis. So another cause or an incident was needed to bring on war. As the crisis was seemingly being defused, President McKinley sent an American warship on “a goodwill” mission to Cuba. (This is a variant of the misguided leadership that led to the start of the disastrous Mexican-American War of 1846. Two countries are at odds over a border region. So they put armed forces close to each other. Someone starts shooting. Both blame each other. Blood is shed. War begins).

The Maine blew up in Havana harbor. Spanish sailors jumped into the water to save Americans. Yet Americans, a few months later when war began, would be trying to kill those would-be Spanish saviors. That’s because the destruction of the Maine, along with intense jingo pressure in Congress and the media, led McKinley to ask for war. The destruction of the Maine was a setup. An American naval board quickly claimed a mine destroyed the Maine. Hearst’s publications wrongly blamed the Spanish. (xvii) That was enough to push the country into war.

Yet years later all the evidence pointed to no mine and more likely an internal explosion (“In the reports we have examined, we have found no technical proofs that an external explosion caused the destruction of the Maine. The existing proof points to an internal explosion,” wrote Admiral Hyman Rickover, (xviii) quoting a 1975 report). This lie of a mine destroying the Maine was matched some 66 years later. That’s when the Gulf of Tonkin incident also wrongly led America into the war in Vietnam because one of its ships supposedly had been attacked. “History,” wrote Acton thinking of the war lovers mentality, “has done much to encourage the delight in war. The motive has been to make men willing to fight and dissimulate the discouraging facts. (xix)

Unfortunately, some Americans viewed the slaughter of this short war in which few Americans died in battle with the Spanish (xx) as a good thing. For instance, a professor of government, Woodrow Wilson, would call the war “just, inevitable and “glorious.” (xxi) Wilson wrote that “it was for us a war begun without calculation, upon an impulse of humane indignation and pity.” (xxii) The quick one-sided victory for the Americans was called “the splendid little war” (xxiii) by John Hay, a secretary of state in the McKinley and Roosevelt administrations.

But what was splendid about avoidable killing, about going to war with a nation that didn’t want to fight? Spain had no desire to battle America, or anyone else, in 1898. It certainly wanted to settle the issue diplomatically and was unprepared for war. Its navy was so decrepit that it sailed into battle with its leader, Admiral Cervera, knowing it would have “neither base, nor coaling station, nor transport ships, nor any of the most elementary requisites for a fleet to exist, let along fight.” (xxiv)

America in 1898 also finally took Hawaii, ignoring the objections of former President Cleveland. It was embracing empire, with all its military and imperial implications. “We are all jingoes now,” wrote the New York Sun, “and the head jingo is the Hon William McKinley, the trusted and honored Chief Executive of the nation’s will.” (xxv)

Yet some Americans still opposed empire. And, by the 1920s, they attempted to restore an “isolationist,” non-interventionist, tradition. And that meant a small military, only designed to protect the nation. Why would there be revulsion with war and empire in the 1920s? (xxvi) Millions of Americans were disgusted by the thousands of senseless American deaths in the next war. That war would be very different. It would be fought against well-armed countries, unlike the Spanish in 1898. These nations’ armed forces were well equipped to kill and maim lots of Americans.

Indeed, the Great War, WWI, was neither splendid nor was the depression that followed it.

End of Part II

Link to Part III: https://gregorybresiger.com/what-next-and-next-a-shorthand-history-of-america-at-war-part-iii-america-and-the-great-war-1917-1918/

____________________

(i) “The Folly of Empire: What George W. Bush Could Learn from Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson,” John B. Judis, p 29 (Scribner, New York, 2004)

(ii) Graebner Ibid.

(iii) See “Honor in the Dust: Theodore Roosevelt, War in the Philippines and the Rise and Fall of America’s Imperial Dream,” Gregg Jones, (New American Library, New York, 2012) . Also see “The Folly of Empire,” John B. Judis: What George Bush Could Learn from Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson” p 67, (Oxford University Press, New York, 2006).

(iv) Judis, Ibid.

(v) “The Conquest of the United States by Spain,” Mises.org. December 14, 2006

(vi) See “Citzen Hearst,” by W.A. Swanberg, p131-132 (New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1961). Hearst screamed for war and rejected every proposal for Cuban autonomy. He wrote that ,“Cubans who cooperated with the new Spanish schemes would be considered traitors to the republic.”

(vii) “The First Casualty,” Philip Knightley, p56, (Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich, New York, 1975)

(viii) An example of this was Edward Atkinson, a member of the Anti-Imperialist League, who wrote in 1898 that “Commerce is today the prime factor in the world’s work. Its development is the chief object of nations,” See “Twelve Against Empire. The Anti-Imperialists, 1898-1900,” p 93 (McGraw Hill, New York, 1968).

(ix) From “Imperialism and Social Classes,” Joseph Schumpeter , (New York:Meridian Books, 1955), p90. Schumpeter writes that “the type of worker created by capitalism is always vigorously anti-imperialist.” Also see “Commerce Defended,” by James Mill at Mises.org

(x) Imperial Democracy,” Ernest May (Harper Torchbooks, New York, 1961) “The autonomic constitution…gives to inhabitants of the island of Cuba a political system at least as liberal as that which exists in the Dominion of Canada.” p 157

(xi) See The War of 1812 by Harry L. Coles (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1965)

(xii) “The Politics of War. The Story of Two Wars Which Altered Forever the Political Life of the America Republic,” Walter Karp, (Harper & Row, New York, 1979).

(xiii) “Without war,” complained Helmuth von Moltke, “the world would deteriorate into materialism.” See “Why They Hate,” Ron Paul, Mises Daily 5/17/14 at Mises.org.

(xiv) “The War Lovers: Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst and the Rush to Empire,” Evan Thomas, (Little Brown and Company, New York, 2011)

(xv) Ibid

(xvi) Theodore Roosevelt’s Story of the United States., Daniel Ruddy, editor, (Harper Collins, New York, 2010), pp235-242

(xvii) Citizen Hearst, Ibid.

(xviii) See El Maine y La Guerra de Cuba,” H.G. Rickover (Susaeta Ediciones, S.A. Barcelona, Spain, p 175, Ausencia de restos de mina or de torpedo. En ningun lado se menciona que hubiera restos de receptaculo de una mina o de un torpedo. Si hubiera explosado una mina o un torpedo de tamano considerable, se habrian encountrado algunos restos de su receptaculo.

(xix) Lord Acton,” Roland Hill, (Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, 2000)

(xx) Of course, these minimal numbers lost in battle with the Spanish don’t include the thousands of Americans who died or were injured in the succeeding revolt against the Americans in the Philippines and the Americans who died from the bad meat in army supplies.

(xxi) See Wilson, A Scott Berg, p 130, G.P. Putnam & Sons, New York, 2013

(xxii) Ibid

(xxiii) “All the Great Prizes: The Life of John Hay,” John Taliaferro, (Simon & Shuster, New York, 2013)

(xxiv) See Spain, A Modern History, Salvador de Madariaga, pp72-87 (Frederick A. Prager, New York, 1958)

(xxv) “A Diplomatic History of the American People,” Thomas A. Bailey, p 459, (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1980).

(xxvi) For a description of this tradition and the Americans who believed in it, see “Twelve Against Empire: The Anti-Imperialists, 1898-1900,” Robert L. Beisner, (McGraw Hill, New York, 1968)

![]()

1 Response to "What Next? And Next? : A shorthand history of modern America at war, Part II America Becomes an Empire"

[…] Link to Part 2: https://gregorybresiger.com/what-next-and-next-a-shorthand-history-of-modern-america-at-war-part-ii-a… […]