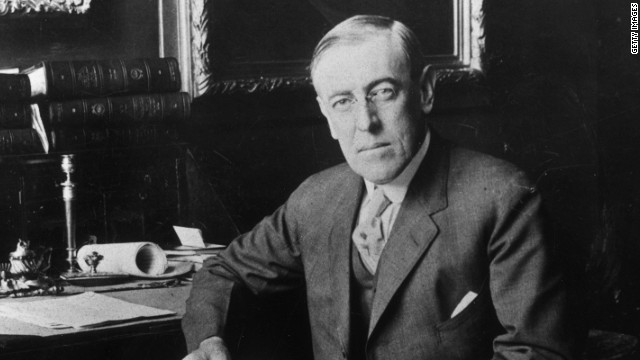

President Wilson, at the outset of the war in Europe in August 1914, called for strict neutrality. “We must be impartial in thought as well as in action,” (i) he announced. He knew most Americans wanted to stay out of the war. The same was true some 25 years later at the start of World War II as well as 25 years after that when America was quietly expanding its role in the Vietnam War.

Indeed, President Wilson ran for re-election, some two years after WWI began, in November 1916 on a peace plank. He emphasized that he had kept the nation at peace so Americans weren’t becoming cannon fodder. However, five months after his re-election, he sought a war declaration. Wilson called for “a crusade” to make “the world safe for democracy.” (ii)

Why the change?

Actually, Wilson’s neutrality had been questionable almost from the beginning of war. Indeed, between 1914-1917, he quietly became more and more pro-Allied. He complained little about Allied violations of American shipping while becoming more critical of German violations. Still, his pacific secretary of state, William Jennings Bryan, was disliked by the British government. That’s because Byran, determined to keep American out of war, resigned in frustration in 1915. He saw the pro-Allied bias of Wilson’s policy. It included allowing American banks to extend vitally needed loans to the Allied nations, some of which were going broke. (iii)

“I thought,” Bryan later wrote, “they (the loans) violated the spirit of neutrality because money, being able to purchase all other contraband materials, was in effect the worst of contraband,” (iv) Bryan also objected to Wilson’s insistence that an American citizen had the right to travel in the war zone. That, Bryan feared, was a policy that “could involve his country in war.”

Wilson’s ambassador to the Court of St. James, Walter Hines Page, was strongly pro-British. “A government can be neutral, but no man can be,” Page wrote to his brother. (v) He was not neutral. For example, Page would go over critical dispatches from America with British officials. He would advise the British on how they could most effectively answer American complaints.

As much as the British government criticized Bryan, it loved Page. Lord Edward Grey, the British Foreign Minister through most of the war, has several pages in his memoirs praising Page. (vi) Winston Churchill in his memoir of World War I, also lauded Page. Churchill was delighted when the war began in 1914. He also scoffed at anyone in America who opposed the war. (vii)

While America was still officially neutral until April 1917, Wilson sent his close adviser Colonel Edward House—-who was the de facto Secretary of State (viii) —-to Europe. House signed a friendly memorandum in 1916 with Grey. Here was memorandum that reflected America’s true policy. And it certainly was not publicized as Wilson ran for re-election on a specious peace plank (This was similar to Lyndon Johnson’s deception some 48 years later. He campaigned as the peace candidate against Senator Barry Goldwater, often saying little about Vietnam, except that American troops should not be sent there. (ix) He then won a landslide victory. Later he sent hundreds of thousands of troops to Vietnam).

The U.S., House told Grey in reviewing the memorandum, would propose a peace conference of all warring parties. And if the Germans declined to attend, then the United States would probably join the war on the Allies’ side, House said. But what if the Germans came to the peace conference?

“If such a peace were held, it would secure peace on terms not unfavorable to the Allies; and, if it failed to secure peace, the United States would leave the Conference as a belligerent on the side of the Allies, if Germany was unreasonable,” House wrote. (x)

These were not the actions of a neutral government, a government that sought to spare its citizens the agony of a terrible war. This was the thesis of Congressman Claude Kitchin in voting against war. He said that the war would bring “one vast drama of horror and blood.” He also believed “that we could have and ought to have kept out of this war.” (xi)

Entering the war in April 1917, the U.S. was the deciding force in the victory of the Allies. The Allies were on the point of financial collapse. They required additional infusions of American capital. They also needed American manpower. That’s because their armies had bled and bled owing to the blunders of their leadership. Russia, Italy and Serbia were at the breaking point. Britain was close to being starved into submission by German U-boats, which the British admitted after the war.

The Allies had consistently said the Central Powers wanted to impose German militarism on Europe and much of the rest of the world; to destroy the Allies’ lands and colonies. Germany certainly had very broad war aims that probably would have made her the dominant power in Europe. But what about the Allies’ war aims? Were they really so different?

World War I treaties called for the victorious allies to carve up the Ottoman, German and Hapsburg Empires as well as ignore the pleas for liberty of various peoples including the Kurds, Vietnamese and Irish. The Chinese, who refused to sign the World War I peace treaty at Versailles, lost lands to Japan, who were paid off by their Allies for their help against Germany during the war.

The Allies, says a historian of the Versailles peace treaty, made decisions that set the stage for endless hatreds, especially in Asia and Africa. (xii) Most of the successor states to the Ottoman and Hapsburg Empires were unstable, yet President Wilson wanted the United States to be a lead player in carving out new European and Asian nations. Still, many Americans, as measured by post-war elections, had enough of their president trying to re-make the world in his own image. (xiii)

Americans would become disillusioned after World War I as they would after so many other wars and near wars to come. Wilson lost favor with the American people. The nation was stuck in a depression after World War I (It was a depression that was reversed not by the recommended but unexecuted counter-cyclical Keynesian policies proposed by Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover—he would try those policies without success about a decade later as president during the Great Depression—but owing to laissez-faire policies the Harding administration. These are detailed in Joseph Schumpeter’s book, Business Cycles). (xiv)

After the war, many Americans were disgusted with Wilson. They rejected his proposals for new military alliances and a League of Nations that would intervene to keep the world stable. These were part of his system for establishing world peace under American leadership.

However, there were domestic consequences to Wilson’s plan for a new world order. Numerous war dissenters were jailed, many illegally. Wilson allowed his attorney general, Mitchell Palmer, to make a mockery of the Bill of the Rights. (xv) Many Americans were fed up by the end of World War I in 1918. The president’s candidates in Congress lost in both the 1918 and 1920 elections.

“By the end of 1919 half the country would have cheered his impeachment. A madman and a criminal, that was what millions of Americans now thought of the president,” wrote journalist and historian Walter Karp. (xvi) Wilson also refused a pardon to perpetual socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs, who was admired by many because of his courageous and peaceful opposition to the war. The president was thoroughly rebuked, Debs said. He (Wilson) “was the most pathetic figure in the world,” Debs said. (xvii)

Wilson left office detested by millions of his countrymen. This would also happen to other war presidents, including Truman, Lyndon Johnson, Nixon, both Bushes and countless other chief executives. They gave their nations useless wars—wars they seemed popular at their outset and later destroyed their reputations, ending their political lives. The same had happened to Lord Aberdeen, who led the British into the horrific Crimean War. (xviii) Some democrats pledged to run for election in 1920 on Wilson’s support for the Treaty of Versailles. They lost.

Many Americans, in the 1920s and 30s, wanted to go back to a traditional, non-interventionist foreign policy. It would take an admirer of Woodrow Wilson to destroy this strong non-interventionist sentiment. We’ll meet him in our next segment.

End of Part III

Link to Part IV: https://gregorybresiger.com/what-next-and-nexti-a-shorthand-history-of-modern-america-at-war-part-iv-world-war-ii/

_______________________

(i) The Political Thought of Woodrow Wilson, E. David Cronon, editor, p 301, (Bobbs-Merrill Company, New York)

(ii) Ibid.

(iii) See “The Pity of War,” Explaining World War I,” Niall Ferguson, (Basic Books, New York, 1999)

(iv) ”The Memoirs of William Jennings Bryan,” by himself and his wife Mary Baird Bryan, p 376 (John Winston Company, Chicago, 1925)

(v) “Wilson,” A. Scott Berg, p 337, G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 2013). Also see “Walter Hines Page, the Southerner as an American, 1855-1918,” John Milton Cooper, Jr.. (University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, 1977) pp 286-287. A few months into the war Page would write to Wilson of the Germans that they were “another case of Napoleon—even more brutal; a dream of universal conquest.” He also urged that Prussian militarism must be “utterly cut out, as surgeons cut out a cancer. And the Allies will do it—must do it, to live.”

(vi) “Twenty Five Years, 1892-1916,” Viscount Grey Falldon, Vol II, p 102, (Frederick A. Stokes Company, New York, 1925)

(vii) “See “The World Crisis” by Winston S. Churchill, (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1923), p 426. He contemptuously writes of American opponents of the war, in effect, saying there was little opposition to the war: “Pacifism, indifference, dissent, were swept from the path and fiercely pursued to extermination; and with a roar of slowly gathered, pent up wrath which overpowered in its dint every discordant yell, the American nation sprang to arms.” p 704

(viii) “Wilson,” Berg, p 385

(ix) “Vietnam, a History,” Stanley Karnow, (Viking Press, New York, 1983), p 395. Even as he promising to stay out Vietnam, Karnow notes, his advisers were planning to enlarge the war.

(x) Grey, Ibid.

(xi) ”The Costs of War, America’s Pyrrhic Victories,” John V. Denson Editor, pp503-508 (Transaction Publishers (New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1999)

(xii) “Paris 1919. Six Months that Changed the World,” Margaret McMillan, (Random House, New York 2001). Wilson deferred to his British and French allies and their imperial problems. He gave no time to the Vietnamese who asked for a hearing about their complaints about the French Empire. And as to the Irish rebels, trying to win their freedom from the British Empire, “When a delegation of nationalist Irish asked him for support, he felt, he told his legal adviser, like telling them to go to hell.” p 11. That should not have been surprising since the French ambassador had previously said of Wilson that he was “a man who, had he lived a couple of centuries ago, would have been the greatest tyrant in the world, because he doesn’t seem to have the slightest conception that he can ever be wrong.” p5. McMillan concedes the Allies had a difficult situation in carving up Europe. However, “By their offhand treatment of the non-European world, they stirred up resentments for which the West is still paying today.” She also complains that in Africa “they carried on the old practice of handing out territory to suit the imperialist powers. In the Middle East, they threw together peoples, in Iraq most notably, who still have not manager to cohere into a civil society.” p493

(xiii) “Woodrow Wilson and World Politics,” N. Gordon Levin, p 1, (Oxford University Press, New York, New York, 1967).

(xiv) See my article “Two Ways to Fight a Depression,” which relies heavily on Schumpeter’s analysis of the recovery from the 1921 depression. FFF.org.

(xv) See “The Politics of War. The Story of Two Wars Which Altered Forever the Political Life of the America Republic,” Walter Karp, (Harper & Row, New York, 1979) pp331-339. Also see “Political Hysteria in America: The democratic Capacity for Repression,” Murray Levin, (Basic Books, New York, 1971).

(xvi) Ibid

(xvii) “When the Cheering Stopped—The Last Years of Woodrow Wilson,” Gene Smith, p 156, (William Morrow and Company, New York, 1964)

(xviii) For more on how the British government of Lord Aberdeen was destroyed, see my “Laissez Faire and Little Englanderism” in “the Journal of Libertarian Studies,” Volume 13, Number 1, Summer 1997 at Mises.com Also see “Economics and the Public Welfare, a Financial and Economic History of the United States 1914-1946,” by Benjamin M. Anderson, pp90-91, (Liberty Press, Indianapolis, 1979). Also see Karp, pp 333-335 for Wilson’s loss of popularity.

![]()