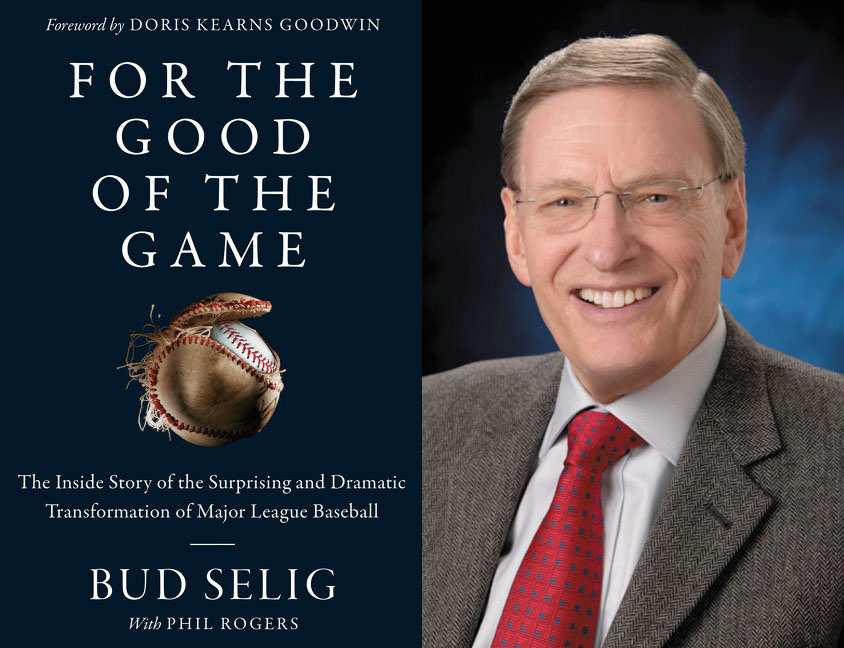

Title: For the Good of the Game

Subtitle: The Inside Story of the Surprising and Dramatic Transformation of Major Play Baseball

By Bud Selig with Phil Rogers

(Harper Collins, New York, $28.99, 315 pages,)

Bud Selig, longtime baseball team owner and later major leagues baseball commissioner for some 20 years, says the national pastime he loved from his childhood in Milwaukee was a mess when he became commissioner in 1994.

Actually, he has a colorful way of summing up baseball’s parlous condition: “On the business side, I inherited a f… nightmare.”

What makes this book a compelling read is Selig’s uninhibited criticism of so many in and out of the game. He rips fellow owners, some union leaders, his immediate processor as commissioner and even squeezes in a bad word for Vice President Gore’s flawed intervention in the great baseball strike that derailed the World Series.

However, before the season prematurely ended, a federal mediator seemed to have hammered out a deal, but the vice president went back on it, Selig says. He gave the vice president a piece of his mind.

“What did you just fucking say to me?” I snapped at Vice President Gore. “You’re tired? You’re tired. You guys gave me your word.”

No World Series

The World Series wasn’t played in 1994 because of the strike. No World Series is something that had never happened before or since (The Series had even been played during World Wars I and II, but the Hessians, the players, and Hustlers, the owners, saw that it didn’t happen in 1994).

What had gone wrong for baseball by the mid 1990s? A lot.

This was an era of strikes, juiced up sluggers and myopic owners. And many of the owners, who Selig claims didn’t understand the importance of competitive balance, fought him over the need for revenue sharing.

Football Triumphant

Yet revenue sharing was a principle of sharing some of the bucks so every team could have shot at winning. It was an idea that football had embraced over a generation before. Football’s most important, powerful owners by the early 1960s understood and accepted that sharing revenue led to competitive balance. This gave every team’s fans hope that, although their team might reek one year, they could still dream about next year.

Why was football more competitive?

In part it was because of football’s draft system, which calls for the worst team to draft first the next season. That combined with a sharing of various national television revenues gave hope to this year’s losers that the cry of “wait next year” cry was realistic.

Selig credits this balanced approach as one of the reasons why football in the 1960s and 1970s became wildly popular. It was in this period football passed baseball as the most popular sport in America and football hasn’t looked past since.

Need proof?

What has been the most popular event on American television for about the last twenty years? The Super Bowl. It has become more than a game but an event around the country, with tens of millions of Americans holding Superbowl parties. Even people with little interest in football get caught up in the Superbowl mania.

One could say the same for the World Series. It is sometimes popular, depending on the teams battling for the brass ring and whether the series goes the maximum seven games. But it doesn’t have the pull of the Superbowl or the weeks of football playoffs leading to this last championship game of the year.

The Sorrows of a Baseball Fan

By the way, I say this with sorry. I grew up in a very different country in the late 1950s and early 1960s. That’s when baseball was tops and football wasn’t even number two. Boxing, now a bit of a joke sport, was number two behind baseball.

Selig also criticizes his predecessor as Commissioner Fay Vincent. He claims Vincent was afraid to raise the revenue sharing issue because he feared the hostility of the owners of teams with the biggest revenues. The owners hire and fire the commissioner. The commissioner is the owner’s man, not the fans’ nor the players’, the latter of whom have their own leaders.

Selig also blames some of the players for the problems of baseball. He says they were led by union leaders who saw nothing wrong with the use of illegal steroids.

One union chief, he complains, equated steroid use with smoking cigarettes. This leader constantly blocked efforts to test players. Many fans wanted testing because this was a time when many players were suddenly bulking up and breaking homerun records. It was a far cry from Selig’s formative years as a baseball fan in the 1940s and 1950s.

Selling Cars

Selig was a Milwaukee car dealer who grew up a Yankee fan because his city had no major league team. But he was delighted in the early 1950s when the Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee. But major league baseball can give and take. The Braves moved to Atlanta after about 15 years in Milwaukee.

Selig was immediately off and running to bring major league baseball back. In 1971, it was restored when the Milwaukee Brewers started playing. The story of bringing baseball back is an intriguing part of the book.

But I think the best parts of the book are when Selig’s takes on fellow owners, on whom he can be rough, and also torpedoes former commissioner Fay Vincent as well as strongly criticizing labor leaders like Donald Fehr and Marvin Miller.

Labor Says no Testing

The labor leaders did everything in their power to oppose drug testing. That nearly led Congress to step in and discipline baseball at the height of roids crisis. Baseball enjoys an exemption from the anti-trust laws and an angry Congress could have taken that away. But major baseball, under considerable public pressure, finally accepted mandatory testing.

Selig has mixed feelings about Miller. Selig says Miller should be in the Hall of Fame, because he obtained much better pay and working conditions for the players. And I believe he respects him for that and also believes some of his fellow owners were fools to oppose better pay and working conditions for players.

The owners were “relentless in the belief that they should control all of the power of the sport,” Selig complains.

However, on the down side, Miller never grasped the dangers of the roids problem, the author says. One might have said the same thing about Selig and his fellow owners, who were happy with lots of homeruns and lots of happy fans.

But when Miller retired, his successors felt honor bound to oppose all testing. One baseball union leader said roids were no more dangerous than smoking cigarettes so any testing was unjustified, an invasion of the player’s personal freedom. This came at a time when all sorts of players were bulking up and suddenly hitting long homers when they had never done that before.

Selig now says baseball has a very good testing system and that a new, expanded playoff system combined with revenue sharing are leading to a better, healthier business.

Do I believe that?

Not exactly.

The Persistent Woes of the Game

I think the game is going in the right direction and Selig deserves credit. However, football is still number one by a country mile and baseball’s television ratings still lag football. Long term, I can see problems for baseball that Selig has probably only delayed. As a livelong lover of baseball—I went to my first games at the Polo Grounds and Yankee Stadium—I hope I’m wrong.

But, looking at television ratings and asking young people about their sports preferences, I’m afraid I’m not.

![]()