I grew up in the late 1950s and early 1960s on a hill in the Southwest Bronx neighborhood of Highbridge, which overlooked a magical place called Yankee Stadium. To a skinny little boy of four, it seemed gargantuan.

It was. When it opened in 1923, an impressed Babe Ruth, surveying this magnificent new baseball palace, supposedly said, “some ball yard.”

And it was. Some of the greatest moments of my youth were when my saintly father—-who was working countless jobs and would eventually get his family out of Highbridge as the neighborhood was collapsing in the 1960s—-would take me down the hill. We’d follow Highbridge’s main drag, Ogden Avenue. And there, as the avenue ended at the bottom of the hill, one looked up and saw a massive ballpark that would impress any four-year old who was beginning a baseball love affair that still is going strong generations later.

Yankee Stadium was the House built by “the Bambino,” as some Italians called Ruth. It was where the great Joe Dimaggio, the Iron Horse Lou Gehrig, Tony “Poosh em up” Lazzeri and countless other greats had played. It was where I spent some of the greatest moments of my youth or any time in my life. Although my father was a hard working man, he must have been able to manufacture time. He seemingly worked all the time, yet he still took me to many Yankee games. And any game sitting alongside my saintly padre, a baseball encyclopedia, was a good one.

But the best games of all had to be a baseball institution now almost gone, but fondly remembered by many of my generation: the Sunday/holiday doubleheader. It was a revered institution of my youth. However, it is now all but kaput. That’s because major league baseball—-long since dominated by the hustlers and the Hessians—respectively the mostly myopic club owners and the players under the control of their union, which stood in the way of steroids testing until Congress threatened to intervene—-long ago decreed the demise of the regular doubleheader.

These days Sunday doubleheaders are now about as common as telephone booths, honest pols and watching or listening to major media for more than five minutes without countless moronic messages imploring one to play the lottery or trying to persuade more suckers to rush to a nearby casino.

But the Sunday doubleheader wasn’t a sucker’s play. It was simply great. Average people could go and see their favorite team play two games for the price of one. This was a time when baseball was one of the better, if not the best, sports buys around. A father or a mother could treat a child to a magnificent day for just $5. We would sit in those great bleachers for seventy five cents apiece. That left $3.50 to buy hot dogs, soda and anything else we wanted. In those days of yore, one wasn’t assigned a seat in the bleachers at Yankee Stadium. One paid for admission and then could wander all around the bleachers.

And, at the end of the right field bleachers, one could stick one’s head out and see the Yankee bullpen. At the other side was the visiting bullpen. Once, when the Washington Senators team was playing the Yankees—and playing for the Senators in those days was the equivalent of playing in baseball Siberia—-I stuck my head in and saw pitcher Bennie Daniels warming up. He didn’t appreciate my questions and made some off-color comments that led me to restrict my visits to the Yankee bullpen.

The regular Sunday doubleheaders usually began around Memorial Day. They continued through the summer right up to the end of the summer on Labor Day. Whether on the road or at home, if it was Sunday—-or a holiday such as the Fourth of July—-your team played two games beginning at one o’clock. My father and I could hardly wait. Indeed, we would get down the hill early, arriving at the ballpark around 11 in the morning.

Why so early?

It was great to sit in those bleachers with my father, who could weave endless tales of long gone players and events. He was an old New York Giants fan who never stopped rooting for his beloved “Jints,” even after they moved 3,000 miles away.

When he was very young his father had died. Afterwards, a kindly uncle had taken him to the Polo Grounds as a little boy in the early 1920s. He had fallen in love with the great Giants of that era, “King” Carl Hubbell, Bill Terry and Mel Ott. He was hooked on baseball. Now he was passing on this bonding baseball experience to his son. And the Sunday doubleheader of the 1950s and 1960s was the crown jewel of this heavenly experience.

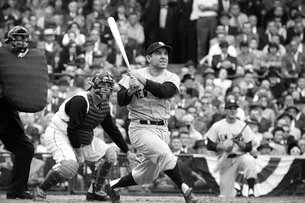

Back in those days you could see home-team batting practice, something you generally can’t do today thanks to the mindlessness of the Hessians and the hustlers. Batting practice was a kind of extra show your team put on for you before the game. And what a show it was! This was the team of Yogi Berra, Elston Howard, Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle. Mantle was a star one never wanted to miss. The sound of the ball coming off Mantle’s bat seemed more violent and destructive that any other player’s. It was incredibly powerful.

At a little after one, the first game would begin. There was a unique strategy in playing doubleheaders. Managers would often hold out players in the first game so they would be available in the second one or they might take a player out early in the first game so he would be fresh for the second game. It was difficult to sweep doubleheaders. Most of them seemed to end in splits.

At around 3:30 or 4, the first game would usually end. Games went faster in those days. There weren’t as many pitching changes and batters weren’t stepping out every five seconds (One player in the 1970s, Mike Hargrove, would step out and adjust his batting glove so often that he was known as the “human rain delay.”).

Players would go into the clubhouse between games to rest for about 30 minutes while the ground crew would work on the field. At around 4:30, the second game would begin. We would stay until around six and then, reluctantly, we would head up the hill for home.

My father would have a transistor radio in hand so we could listen to the last innings of the game. We would arrive home around 6:30. My kindly mother would have dinner ready for us in the living room. The set would be tuned to channel eleven, which carried the Yankee games—-and before that the Giants games. We would have our dinner and watch the end of the second game.

Win or lose—-and usually it seemed it was a win and a loss for my beloved Yankees, or I as would call them, “The Highbridge Heroes—-it had been a great time, a memorable time. Duff Cooper, the air minister in the Chamberlain government who famously resigned after the disgraceful Munich settlement of 1938, entitled his memoirs “Old Men Forget.”

This is one old man who will never forget.

![]()

1 Response to "What’s Wrong with Baseball, Part III: Why can’t we go home again on Sundays?"

[…] previously written about in these pages, thanks to the efforts of my Irish partner, Liam Judge. ( https://gregorybresiger.com/whats-wrong-with-baseball-part-iii/ […]