(G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 290 pages)

Who was the hockey player Bobby Orr?

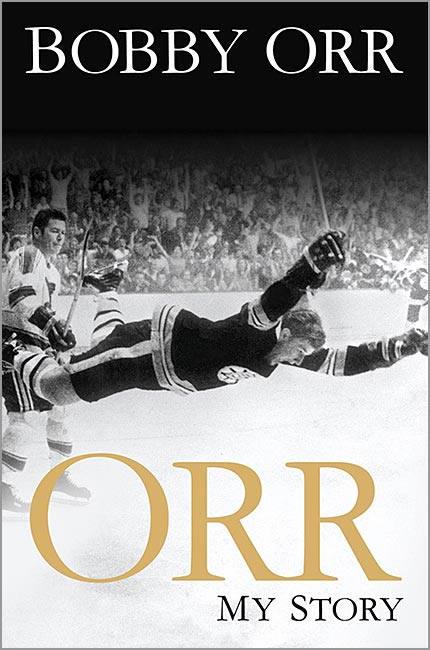

Finally, with the publication of Orr’s autobiography, there is a chance to answer the question.

For a young generation of sports fans, Orr is today spoken of by their elders as a mythical figure as Eddie Shore, Joe DiMaggio or Babe Ruth were for me when I was a child in the 1950s. Then it was my father speaking of the great players of his youth. Now I’m the gray hair spinning myths to the youngsters (Full disclosure: Even though I grew up in a New York Rangers household, I’ve been a Bruins fan since I was about 13, which is now close to a half century).

Who was Bobby Orr?

He was a slender polite, incredibly shy young man who revolutionized hockey almost fifty years ago, changing the role of the defenseman forever. In the course of a relatively short career—-he began as a teenager playing for the Bruins in 1966-67 season and was basically done about a decade later—he changed hockey forever.

Orr came to the National Hockey League looking like anything but a defenseman. The latter was usually a beefy guy whose main job was to rough up attacking forwards and stop them from setting up housekeeping in front of their goaltender. A defenseman was usually someone who could double as bouncer in the tough parts of town and possibly did. Hockey players in that era were usually underpaid so most had off-season jobs. Defensemen were generally poor skaters and rarely if ever scored. The slender Orr could pass, score, but could also mix it up with the best of them.

“As a young player in the NHL I was called out on certain occasions and responded to those challenges to fight because I felt it was my duty to do so,” Orr writes. “I didn’t particularly enjoy fighting, but I understood its place in the game. I never wanted or needed someone covering for me when the rough stuff started, and as a result I believe it helped me over the course of my career, both with teammates and opponents.” (p249)

Orr’s fists, his remarkable skating—-it was said Orr could skate faster backward than a lot of guys could skate forward—-his incredible ability to see the entire rink and know where to pass or shoot, changed the fortunes of what had been a sad sack team called the Boston Bruins. The Bruins were once a great team in the 1930s and 1940s that had started to go downhill at the end of the 1950s.

From 1959 they missed the playoffs for eight straight years through much of the 1960s. In that period Boston became the equivalent of hockey Siberia. The team almost always finished sixth in a six team league in which the top four teams made the playoffs. In these dark days of the Bruins, one year they finished fifth, just barely avoiding their customary basement position. And that was actually considered a good year, even though they didn’t make the playoffs.

The arrival of the wunderkind Orr in 1966, who the Bruins had been scouting since he was about 10 years old and who the Toronto Maple Leafs had passed on the because he was so small, changed the fortunes of the sad sack Bruins. The Leafs started to decline—-they haven’t won a cup in 47 years and didn’t even make the playoffs this year. The Bruins, in Orr’s second year, 1967-1968, finally made the playoffs. Two years after, they finally returned Lord Stanley to Beantown in 1970 after a 29 year absence. The Bruins, who in their sometimes proud history that has never included back-to-back championships, seemed on the verge of a dynasty.

It never happened.

First, the idiot Bruins’ management played hardball with their coach, Harry Sinden. And, over a lousy $5,000 raise, they lost the coach who had helped them win the cup for the first time in decades. Still, the Bruins, the next year, had a fabulous regular season. They seemed ready to repeat. Then, as so often happened in Bs history, they were upset in the playoffs by the glorious ones, the Montreal Canadians. Yet four Bruins, in the regular season, had hit the 100 point mark in that year 1970-71. The Bruins that year even had fourth liners who scored twenty goals, yet they lost in the first round.

What happened?

“But whether overconfidence was the problem, I can’t say” (p 132), Orr writes, saying little about one of the most painful episodes in Bruins’ history.

In my opinion, the Bruins of 1970-71 were one of the greatest teams not to win the cup. However, now over 40 years after the fact, that doesn’t mean anything. The Bruins blew it, in part because the reckless, offense first, style that Orr and the Bruins played would sometimes blow up. Then teams with lesser talent would beat them.

Nevertheless, the next year, 1971-72, the Bruins were a bit more disciplined and won the cup, although, significantly enough, they didn’t have to go through the Canadians. The Habs, through so much of their history, have destroyed the Bruins (That’s why, in 2011, it was so satisfying that the Bruins, in ending a 39-year cup drought, defeated the hated Habs in the playoffs. And that’s why now, on the verge of yet another playoffs series between the Bruins and Montreal, I have removed all the breakables from my abode).

Unfortunately, 1971-72 was the high water mark of the Orr era. The Bobby Orr Bruins ultimately won two cups. Given their talent—-a remarkable group including Derek “Turk” Sanderson, Phil Esposito, Johnny Bucyk and Gerry Cheevers (The cheapskate Bruins ownership let the latter walk. That’s a decision that likely cost the Bruins the cup in 1973-74, when they lost to the Flyers in the final)—-they should have won a few more.

But overconfidence, sometimes shoddy defensive play and Orr’s bad knees meant it was the dynasty that never was. (I define a dynasty as winning at least three championships in a short period and winning at least two championships back to back. That’s something, the Bruins, despite all their talent, have never done).

Bobby Orr, in this much awaited autobiography, takes very little credit for his accomplishments, even though many would argue he was the greatest player in the history of the game.

Was he?

He was the greatest hockey player of my time or possibly anytime (I never saw Shore or Rocket Richard and other ancient greats so how can I say?). He was a Boston Bruins defenseman who broke most of the rules of the game. He was a defenseman who also played offense. Defensemen before Orr rarely joined the rush. Orr often led the rush.

End to end rushes resulting in an Orr goal were his specialty. He played a reckless go for broke style that sometimes succeeded and sometimes imploded, but was never anything but exciting. That, along with more scoring and fighting, are why hockey audiences in the United States dramatically increased in the Orr era. Defenseman was now a glamorous position.

Before Orr, a defenseman who scored a lot might get 30 or 40 points in a year. Orr got 30 or 40 points in a month and normally scored about 120 points a year. He was remarkable, especially on the power play or killing a penalty.

Orr was a sports comet who streaked across the hockey skies, coming and going in a relatively short period. But he left fans sorry that his career ended so soon and in such a disappointing fashion. Orr would have much of his wealth stolen by his odious agent Alan Eagleson. He was a crook who ended up in prison and ousted from the Hockey Hall of Fame. Orr would fail in trying to come back from a series of mistreated knee injuries.

Throughout the book Orr credits others for his success and emphasizes that, effort, is the single most important factor in anyone’s success.“ No one can control what they were born with, but they can control how hard they work. The fact is that talent counts for almost nothing in the absence of hard work.” p72

So was he the best?

No, he couldn’t be.

Why?

He didn’t play long enough, didn’t win enough championships and injuries kept him from living up to his full potential. Nevertheless, any discussion of the ten best ever to play hockey has to include the great Robert Gordon Orr. If he wasn’t the best, he was damn close.

Maybe, like the memory of a long lost happy youth, that’s enough or about as much as any human being can ever hope to get.

![]()