Is Pete Rose a Liar or the Greatest Overachiever in the History of Baseball?

A review of a new biography of Pete Rose.

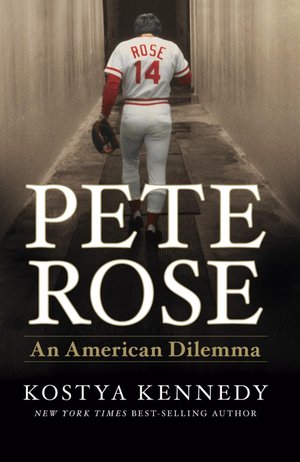

Pete Rose: An American Dilemma by Kostya Kennedy (Time Home Entertainment, 2014, 341 pages) ($26.95)

This book, which profiles a rags-to-riches through hard work athlete, is certainly one of contradictions. One finishes it not sure what to think about this remarkable player. He became a baseball legend who made himself a star by sweat and playing some five positions. Pete Rose ended up with more hits than anyone in the modern history of baseball—-which is over a century old. His playing career qualified him as a first ballot Hall of Famer. But his lying derailed his fast track to Cooperstown.

Rose was a player who always ran hard and who got the most out of his limited talents. Competing players sneered that he was “Charley Hustle.” But he helped inspire teams to six World Series and three championships (His breakup of a double play game seven of the 1975 World Series may be the most significant overlooked play in series history unless it was the remarkable catch he made in the 1980 World Series, helping the heretofore hapless Philadelphia Phillies to their first championship).

However, he also became a wife-cheating sleazeball who ran around with questionable characters tied to illegal bookmaking. That was bad enough. Later, as a manager, he broke the most important rule of a game once plagued by gamblers—-besides betting on the ponies and everything else that moved, he bet on the game he managed. That is despite signs in every major league baseball clubhouse that warns players that betting is the ultimate baseball sin and can get you expelled from this magical game.

Yet away from the betting dives, Rose did fantastic things on the baseball diamond. And it was not necessarily because of his talent but owing to his incredible determination. Yet he ended up disgraced because of his foibles. The worst of which was his lying for some two decades about betting on the game.

Betting is the mortal sin because baseball purists never forget that its premier games, the World Series, were rigged in 1919. That was an event that almost killed the game. However, Rose’s lying also hurt family members—-his ex-wife, his son, Petey, who idolized him, as well as millions of fans who he repeatedly told, over 20 years, that he had never bet on the game as the manager of the Cincinnati Reds. However, Rose later would concede, in the most clumsily unrepentant way in a book (“My Prison Without Bars”) in which made money, that he was lying.

Here is what I concluded after reading this well researched book: Pete Rose is a habitual liar. Pete is a nice guy, retired baseball star, one who treats the average fan with respect. He is a white man who grew up in a society with plenty of racism without a prejudiced bone. Indeed, he enjoyed playing in a game in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, a period when African-Americans were coming to dominate and his club’s management didn’t enjoy Rose’s closeness with black teammates (1). (A black player of that era would say that “Pete Rose was his friend,” not his white friend).

If only these were his only clashes with authority. But Rose is also a man who couldn’t stop gambling from taking over his life. His frequent lies about his gambling contributed to the death of a beloved baseball commissioner, Bart Giamatti. The latter, ironically, loved the game and had loved the hustle of Pete Rose.“Isn’t he great,” Giamatti would say of Rose before the gambling controversies. But later Rose’s woes would be Giamatti’s nightmare. Along with his overeating and limitless cigarettes, the stress of the Rose case would push him into an early grave.

Rose’s betting problems actually began as a highly paid player and drew inquiries from baseball’s security people, who worried that he was becoming dangerously indebted to gamblers. His problems continued into his years as a manager when he bet on his own team. Eventually the weight of the evidence accumulated by baseball, led by attorney/investigator John Dowd, was overwhelming. Rose, despite public comments to the contrary, had broken baseball’s ultimate rule and baseball had the evidence to prove it. Rose signed himself out of baseball. He couldn’t manage or coach. Officially, he could have no connection with the game. Anyone doubting the evidence can look it up on under the Dowd Report. There are the sordid details of Rose’s betting while manager of the Cincinnati Reds.

Still, some may ask this after some 300 pages: Why over decades has baseball imposed this draconian penalty on a baseball icon for betting on the game? There are several reasons.

First, it is illegal and has been for generations. Betting by players or managers or anyone associated with a team attacks the integrity of the game. If fans can’t be sure that there is no fix, then baseball will become pro wrestling; entertaining, but something with a pre-determined outcome. And the lack of predictability—-the potential that every underdog can one day win the big game—-is one of the trademarks of this great game which, unlike most other major sports, is not governed by a clock. So no comeback, in theory, is impossible.

Secondly, baseball is a strategic, long-term game with the longest season, 162 games, of any major sport. One plays for the long term. A manager will often not put his best team on the field on a given night. That’s because some players need rest. This will hurt the team in the short term but help the team over the long term. Say Pete Rose had a big bet on a given game. It could have led him to use players who should have been rested so he could win with his bet, but possibly hurt the team the rest of the season. That is why managers cannot bet on their teams.

Finally, it seems to me that the tragedy of Pete Rose is the tragedy of so many other public figures: Each made a mistake, but would not own up to it. Indeed, in trying to cover it up, the institution or a person makes a bad situation a thousand times worse (An example of that is Watergate, a political burglary that eventually toppled a popular president in 1974 who, just a few years before had won overwhelming re-election in 49 out of 50 states). In Rose’s case, he finally did fess up, but some 20 years after the fact.

What would have happened if Rose had owned up to his very human sins right after baseball proved it had the goods on him back in the late 1980s? (The author, in a conversation with John Dowd, actually raises this scenario). I would suggest that what would have likely happened is that Rose would have been suspended for a year or two by baseball. The commissioner would have asked Rose to stay away from bookmakers and spend a year or two going around and explaining to various groups the dangers of gambling.

If Rose had stayed out of trouble for a few years, baseball probably would have re-instated him and he would have been elected to the Hall of the Fame in the early 1990s. Rose’s reputation would have been resurrected and the lords of baseball, even those who had always been uncomfortable with Rose, would have been happy.

Why?

They could have ended the strange situation we have today and may have forever in baseball. Baseball’s hit leader, officially, can have nothing to do with the game. Go to the Hall of Fame and see the great Mays, Mantle, Aaron, etc. But there’s no Rose.

The author is right. It is a dilemma. It is also a tragedy.

Note:

1) The black members of the Reds, among them Tommy Harper, Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson, liked Pete, the author says, especially when management said he was spending too much time with his black team-mates. Rose ignored management. Indeed, he made a joke of it by shinning Robinson’s spikes. When the great Robinson—-a Hall of Famer and one of the best players I ever saw, in part, because he played every game as though it was his last—-was traded by the Reds in the winter of 1966, it was one of the most idiotic trades ever made. Robinson won the MVP the next year with his new team, the Reds have an opening in the outfield. Rose, a second baseman, offers to go to what had been an all-black outfield. Rose joshed that he was “integrating the outfield.” Rose really hadn’t integrated the Reds outfield. There had been a white outfielder in his name. Still, Rose’s joking shows how he connected with black team-mates.

![]()