A player does well in his first five years and in his first major league years he works on one year contracts.

He pitches well and wins a lot of games. Or maybe he is a position player who has done very well in his first years. Then, just, after he files for free agency or maybe a year or so before he might do so, something important happens for the player, the team and its fans: He signs a long term, guaranteed contract either with the team that signed him and brought him to the major leagues or another team that bid on him.

Guaranteed, But For What?

Now there is a dramatic change: He no longer is working year to year, with every incentive to take care of himself and put up big numbers every year so he can negotiate a better one-year contract next year. Now, for the next seven, eight, or possibly even ten years, the player is guaranteed top dollar, no matter how well or badly he does.

Often, too often, with the long term contract, it is the latter. He never is nearly as good as his first years or so. Or maybe, he does well in his first year or two of his new contract. Then he falls off and is never as good. Still, he continues to get top dollar although he is no longer the player of his great years and likely will never be. And there are many reasons why baseball players who obtain fat long-term contracts rarely live up to their money.

Let me stipulate that baseball players, the same as workers in any other field, should get all they can for as long as they can because one never knows when one’s time is up or when one is no longer in his prime. I say that as someone who has been both the golden boy in workplaces who received nice raises and the bum who was shown the door along with others when a company was going though problems.

However, one can’t ignore the damage done to baseball by the number of times players just don’t live up to their fat contracts. Very few of these players seem to be stealing money—not trying—but most players with long-term contracts, in the course of many years, are at some point not nearly worth the money.

At that point, they are taking up valuable payroll dollars. And those dollars might have been spent on other players who would have given the team a better chance to win than the player with the biggest contract who will never be great again.

The Fans React

What makes it worse—in this era when player salaries are public—is fans and media know which players aren’t earning their pay. And, in their hearts, I believe many of these players know it. But no one is going to give back money.

Let us take a few examples.

I’ll start with my own team. I grew up in the Bronx, a few blocks away from Yankee Stadium. Some of my earliest memories are of going to “the Big Ball Yard” to see Mickey Mantle, “Bullet” Bob Turley and Bobby Richardson. The last time the Yankees won the World Series, 2009, their ace star was C.C. Sabathia.

The winter before he had been signed to a some $20 million a year long term contract, which was later extended by several years. (And, by the way, no one was holding a gun to the head of the Yankees. Indeed, the Yankees had to outbid several other teams for Sabathia’s services).

Good and Then Awful

In his first four years as a Yankee he was very good. He earned his money. Now, in his last three years, his performance has been egregious. The Yankees are a team that, at this writing is plus 15—it has won 15 games more than it has lost and is in line to make the playoffs now—but Sabathia is minus four.

He is four wins and eight losses (4-8). He also hasn’t had many decisions because he has been injured so much and missed starts. And he has been often injured so much because he is considerably overweight. At some six foot and around 300 pounds, he has trouble covering first base, which is the pitcher’s responsibility when a ball is hit to the right side of the infield. (If both the second and first baseman go for the ball, it is the pitcher’s responsibility to cover first. Not covering first was one of the factors in the Yankees losing game seven of the 1960 World Series. Yankee pitcher Jim Coates was slow to get to first base and the Pirates got an extra out that inning. In a wacky last game of the Series, in which the Yankees lost by one run, that might have been the factor that beat the Yankees. Little things, at times, can mean a lot. “For the want of a nail…”).

If Sabathia were a rookie or someone without a long term contract, then, without doubt he would have been sent back to the minor leagues to pitch better. But the Yankees can’t do that: Sabathia, like a lot of veterans who are long past their primes, has a guaranteed long-term contract. The Yankees, the same as many other teams with overpaid players with long term contracts, are virtually married to Sabathia.

It’s Not Only The Yankees

Still, it could be worse. Sabathia, unlike many other overpaid players, is a nice guy who wants the team to win and is regarded as a team leader because he was so important in the Yankees’ championship of 2009.

In the case of outfielder Josh Hamilton, who received a fat contract some years ago from the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim, he was so bad that—even though the team had given him a free agent, five year contract of about $100 million—the team eventually had to give up on him. And the team had to eat most of the contract. The Angels had never obtained anywhere near the big performance that they had expected of Hamilton, a once talented outfielder with the Texas Rangers.

Hamilton’s problem wasn’t weight. It was drug abuse. But, once again, that didn’t matter. He had a long term contract and the Angels had to pay for all those years.

There are various reasons why players with big long-term contracts never pan out. Many aren’t worth the big bucks. Some are injured and never recover. Some don’t care. And some impose big pressure on themselves to perform and find out they can’t do well in a new city. Whatever the problem, it amounts to the same thing: Widespread disappointment that a player never lives up to his premium price-tag.

What’s To Be Done? Pay for Play

Somehow, in the collective bargaining agreement between the players association and the owners, there should be some limitation on the number of years that a player can have, especially when a player is generally in decline after age 30. No veteran player should get more than five years.

However, for the players who are consistently great—say someone like the great closer Mariano Rivera of the Yankees—it would be a very good system. Since they are very good year in and year out, they would have more chances to yank up their salaries. That would be good since they are earning their money. And there would be a closer relationship between recent performance and pay.

There would be fewer instances of the player making the best salary on the team not being anywhere near the best player on the team. Any variant of this proposal should incorporate a pay for play system; a system in which those who are the stars are paid the biggest salaries and those who no longer are the stars are no longer the highest paid.

Would this merit proposal ever be accepted by the players’ union?

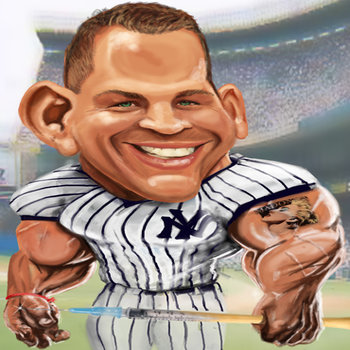

Probably not. But a number of their well-paid members risk becoming pariahs; players who fans are sick of; players they can’t wait for their teams to lose. Indeed, as a Yankee fan, I’m counting the minutes and seconds until Alex Rodriguez (A-Roid) is no longer anywhere near the pinstripes.

![]()